What Can Game Theory Teach Us about Life?

Quite a bit, as it turns out. A couple of well-conceived gaming

experiments initiated half a century ago led to profound insights into human

behaviour. In the 1950s, two American mathematicians (Flood and Dresher)

devised a game called ‘The Prisoner’s Dilemma’. It had a simple premise: the two

players were metaphorically described as ‘prisoners’ suspected of having

committed a crime. Each of them was told that if he testified against the other

(who would consequently be convicted), he would be set free.

The prisoners could not communicate with one another and therefore had three options:

- if neither agreed to testify against the other, they would both receive a sentence, albeit a lighter one for lack of evidence;

- if both testified against the other, they would both get heavier sentences;

- however, if only one testified and the other didn’t, the evidence became unequivocal and the latter would receive the maximum penalty, with the former walking away free.

Which choice leads to the best possible outcome for both players? One might say ‘cooperate’, but since they cannot trust the other would do the same, the ‘rational’ choice – one that fares worse but secures a milder penalty – is for both to testify against the other. If one player is ‘nice’ and the other prone to exploitation, cooperation brings what the game designers coined ‘the sucker’s payoff’.

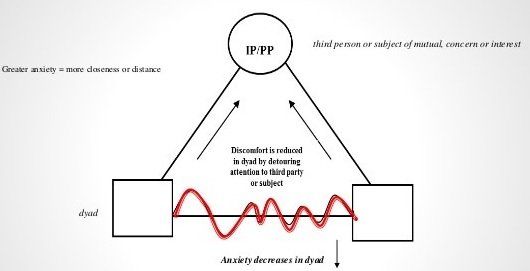

And before you say, pessimistically: ‘nothing new here, we’ve always been told nice guys finish last’, let’s see what mathematicians did next. In the 1970s, Robert Axelrod took the game to its next logical step and initiated an iterative Prisoner’s Dilemma. By being able to examine the choices made in the previous round, each gamer could reflect on the opponent’s intentions or manner of playing: ‘nice’ (cooperators) or ‘mean’ (defectors). Several participants – mathematicians, economists, sociologists, political scientists, behavioural psychologists – were invited to submit their gaming strategies to a round-robin tournament. Some came with rather rigid models: all-nice, all-mean, nice until triggered then all-mean, etc; others with highly sophisticated ones.

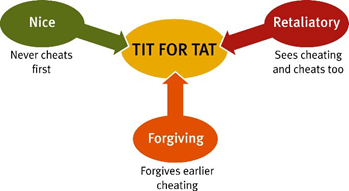

Which was the surprising winner (the game ensuring the greatest payoff)? The simple yet effective ‘Tit for Tat’, where the player would start by being nice (cooperate), then pay in kind, i.e. mirror the opponent’s move. A gaming style that reaps the benefits of cooperation but will not be taken advantage of. Philosophically, this is more reminiscent of the Old Testament’s ‘eye for an eye’ than the Christian ‘turn the other cheek’. On a societal level, this strategy leads to a ‘police state’ that encourages cooperation and punishes ruthlessness in a realistic way that acknowledges the human nature and temptations. But it this really the best way forward? In instances where a player makes an inadvertent mistake, Tit for Tat punishes without second thoughts, leading to a cycle of retaliatory moves that inflict unnecessary pain to both players. Think the Cold War Doomsday scenario brilliantly illustrated in Stanley Kubrick’s film ‘Dr Strangelove’.

In the next and most interesting step, scientists expanded the experiment to mimic a Darwinian ‘natural selection’ phenomenon, in which games that resulted in high overall payoffs could ‘reproduce’ with a probability proportional to their performance. This created generations of ‘nice’ players, ‘mean’ players, ‘tit for tat’, and so on.

What they found was that, at the beginning, the ruthless ruled – ‘survival of the fittest’, you might say. However, Darwin’s theory does not equate ‘fit’ with ‘ruthless’, but with ‘adaptable’ – a distinction that seems forgotten these days. So, after about 200 iterations, ‘Tit for Tat’ started to take over the predators. Further down the line, as players became increasingly ‘civilised’, they learnt the value of altruism – not for some morally superior goal but for their own self-interest – and a variant called ‘generous tit for tat’ (which allowed for some mistakes and was more patient before administering retaliation) emerged victorious. Fast-forward and the ‘game society’ evolved towards a generation of ‘softies’, a sort of ‘Brave New World’ where aggression had been eliminated. The result? The ruthless, or opportunists, emerged again, their tactics taking everyone by surprise.

What do I make of these fascinating experiments? That we humans live in cyclical courses of civilisation, where cooperation is ‘tempered’ by selfishness, but equally, excessive retaliation eventually learns its lessons, leaving room for realistic altruism. Which side of the wave are we riding these days? I am not sure, but game theorists are bound to have a field trip investigating!